Dedicated to the Dark Matter Day.

This brief report is based on the article “Gas kinetics of galactic disks explains rotation curves of S-type galaxies without a need for dark matter”, published in the International Journal of Modern Physics A (2022) v.37, 2250171. Here I explain some details and show that there is no need for Dark Matter (DM) in astrophysics and cosmology. Furthermore, there is no place for DM in astrophysics, because if DM existed, the rotation curves should differ drastically from those we actually observe.

It is well known that DM is mainly needed to solve three problems: 1) “non -physical” Rotation Curves (RC) of galaxies, 2) the observed galaxy clusters, indicating that galaxies are gravitationally bound and belong to their cluster at least for a time comparable to the cosmological one, and 3) Observed gravitational lensing effect observed in galaxy clusters.

The first point in the list mentioned above represents the greatest difficulty, as it clearly indicates that we are missing something essential at the level of the foundations of physics. The problems mentioned in points 2 and 3 are not so crucial and can be solved without the involvement of an artificial DM paradigm. The items 2 and 3 find their solution within the framework of standard physics, since there is a fairly wide margin for maneuver (for details, see the introduction of the article under discussion).

Another point should be mentioned here. According to the cosmologists’ point of view, DM must exist precisely so that the observed structures of the Universe could be formed during cosmological time within the framework of Riemannian geometry. However, on the one hand, the geometry of Riemann is a very specific case of a more general Finsler geometry. On the other hand, nobody promised us that we would be born exactly in the Universe described by Riemannian geometry ( by the way, resent observational data argue for increasing cosmological time). Therefore, such an attempt to preserve the right to work precisely in Riemann geometry (by postulating the existence of DM) seems a bit strange. From physical foundations of Quantum Mechanics it was proved that the geometry of our Universe is not Riemannian. In this case, many of the cosmological problems that arise in the Riemannian world simply disappear if one builds models for the Universe described by a more general geometry with asymmetric connections (in the general case, one should speak about Finslerian geometry). For this reason, within the framework of Finslerian geometry (where cosmological time is much larger than that in the Universe, described by Riemannian geometry), there is enough time to form observable structures in the Universe, and therefore there is no need to involve the DM concept. The problem of the actual geometry of our Universe I will consider next time, and today I analyze the first point of the list (the problem of the rotation curves of spiral galaxies).

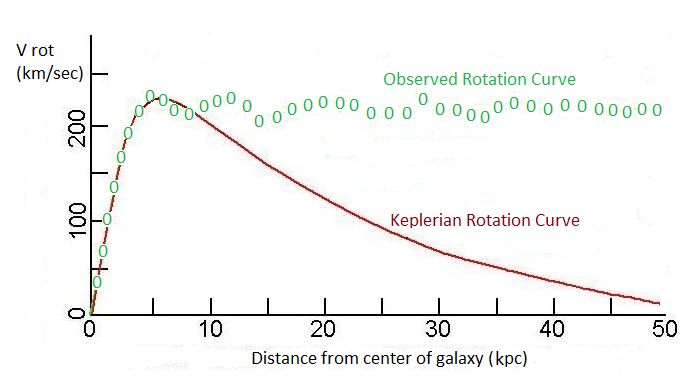

It is well known that until the middle of the 20th century, galaxy observations were carried out only through optical telescopes. With the development of radio-astronomy in the second half of the 20th century, it became possible to observe galactic gas using molecular lines and the neutral hydrogen line (21 cm). This made it possible to draw detailed maps of “non-physical” rotation curves for the outer parts of galactic disks observed in radio. Sometimes the rotation curves (RC) extend up to hundreds of kiloparsecs (one parsec = 3 light years). A typical rotation curve of a spiral galaxy can be seen below (see Figure 1).

Fig. 1. Typical observed rotation curve of spiral galaxy (green open circles) and “Keplerian” one (red solid line). One can see enormous discrepancy between observed and “Keplerian” RCs at large distances (outer part of galactic disk). Distance R_25 for this example of a galaxy corresponds approximately to 10 kps.

Of course, there are also optical observations of rare and remote stars which populate the outer regions, but it is not difficult to show that they will be bounded by host galaxy and will move along elliptical “Keplerian” orbits. Therefore, their movements are easily explained within the framework of classical mechanics. I will return to this topic a little later.

Let us consider a typical spiral galaxy. Since the purpose of this work is to explain the rotation curves of galaxies without involving the concept of DM, I will refer below with the word “matter” only to baryonic matter, reasonably believing that the DM does not exist (because it will not be necessary to explain the rotation curves of galaxies).

It is well known that the matter of galaxies consists mainly of stars (located predominantly in the visible inner part of host galaxy) and neutral hydrogen (HI) which dominates the outer parts of the galactic disk under consideration. This is the neutral hydrogen on whose lines the RCs of the outer parts of the galaxies are observed at 21 cm.

It is rightly believed that the stellar component can be described as a collisionless gas consisting of ideal particles moving in a gravitational field. Until now, it has also been generally accepted that when describing rotation curves, neutral hydrogen can also be described as a collisionless gas interacting only gravitationally. Therefore, the problem with widely used models is that the dynamics of galactic disks is calculated according to an overly simplified scheme, assuming that the global motion of all matter in the galactic disk (we speak of RC) is described only by the laws of Newtonian gravity, unreasonably believing that gas kinetics does not affect the formation of rotation curves. However, it would not be entirely correct to ignore half of the system (gas interaction) and throw out half of the equations describing the system under consideration. Along with the equations of classical mechanics, the description of the galactic disk model also includes the equations of rarefied gas kinetics. /// It should be noted that attempts have been made in literature to estimate the contribution of gas kinetics to global dynamics, but this was wrongly done based on the hydrodynamics (HD) equations, which cannot be applied to describe a rarefied gas (see restriction (3) given below). Furthermore, all relations that are derived from the HD equations and used for a simplified description of a rarefied gas become inapplicable. Since such HD simulations were performed outside the scope of the applicability of the HD equations, they cannot be considered as a credible argument.

In order to understand where the error was made, let’s see how the HD equations was derived. I follow here the standard derivation of the HD equations suggested in the textbook (Course of theoretical physics by Lifshitz and Pitaevsky, volume X “Physical Kinetics” section 5).

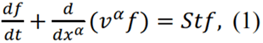

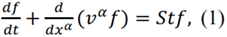

The gas of a galaxy is made of neutral hydrogen. The kinetic equation for one kind of particles is:

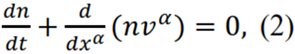

To derive the continuity equation, one must integrate the kinetic equation over the momenta of the particles. However, the integration over the momenta can only be performed under the assumption that all parameters of the system (such as density, velocities, temperature, etc.) change little over distances of the order of the particle’s characteristic mean free path lfp. In other words, from the outset, the domain of applicability of the HD equations is restricted to the case where the characteristic length for the system is Lk >> lfp. Only in this very particular case, the continuity equation can be derived and it will make sense:

To derive the rest of the HD equations, we should multiply the kinetic equation (1) by the momentum (or energy) and then integrate over the momentum. In this case, to perform the integration, the same restrictions must be applied (3):

For this reason (and given that we are only interested in the first equation, since in the case of rotation curves we are dealing with a steady, quasi-stationary motion), the equations with higher derivatives can be omitted, because they do not suggest something new or useful for us.

Thus, the most important point here is that the HD equations can be derived (and therefore can be applied) if and only if the condition (3) is satisfied, which imposes a serious limitation on the applicability of the HD equations.

In the case of calculating the gas dynamics in the outer parts of galactic disk, we are dealing with the kinetics and dynamics of a very rarefied gas, for which condition (3) no longer holds. This means that the HD equations are not applicable (their use leads to an unphysical result). If the HD equations themselves are not applicable, then what should be done? There are many options, I will point out only two obvious ones:

1) Apply directly more general kinetic equations. (this is a cumbersome option).

2) By analogy with the derivation of HD equations, derive more general equations that would be devoid of the indicated disadvantages (simple and clear method). In the work under discussion, I follow this path.

The task of finding the rotation curves of galaxies can be significantly simplified if we take into account the fact that a spiral galaxy is a pseudo-stationary structure. In other words, the disk of galaxy demonstrates a steady state solution. In the case described by the HD equations, this corresponds to a steady flow around an object. It is well known that in this case there is no need to solve all the HD equations. Such steady flows are described by the first (continuity) equation. Thus, in the case of a steady flow of rarefied gas in a galaxy, the solution is also will be given by one equation (some analogue of the continuity equation). Let me briefly outline the derivation of the equation we need to describe dynamics of the rarefied gas. Let’s start with kinetic equations as we did it in the case of the HD approach.

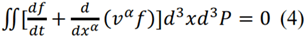

To obtain equation (2), we assumed condition (3) be satisfied everywhere. However, this is not the case for extremely rarefied gas. The quantity (vαf) changes significantly over the mean free path. For this reason, the kinetic equation cannot be averaged over the momenta. Beside this, we are interested in the rotation curve, which represents a global movement of gas. Moreover, we are not at all interested in small-scale turbulent motions. For these reasons, one should average equations (1) over the volume, excluding small-scale motions and making the equations insensitive to restrictions (3):

First term gives dm/dt , where m is mass of gas inside of the integrating volume. Second term can be transformed to

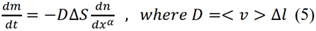

Finally we obtain:

This is a well-known diffusion equation, which in our case serves as a replacement for the continuity equation. The equation (5) no longer suffers from the constraint (3) inherent in the HD approach, and therefore it can be applied to calculate large-scale movements of very rarefied gas (rotation curves) in the outer parts of galactic disks.

We are interested in the outer region of the galactic disk (in Fig. 1, this is the region with R > R_25 = 10 kpc), where there is a large discrepancy between the Keplerian and observed rotation curves, and where the rarefied gas kinetics becomes decisive.

To build our model, we make two assumptions. Both assumptions play against us, i.e., we consider the worst option for us (this is important!).

- In developed model, I do not take into account active star formation at the edge of the optically visible part of galaxy. Since star formation in these regions leads to a depletion of the gaseous component (resulting in a density gradient directed outward of the galaxy), this simplification of the model is obviously working against us. Therefore, if star formation is correctly taken into account, the gas in the outer region of the galactic disk will be even more bounded in galaxy. In addition, it should be noted that we want to describe the RC at large distances from the center. However, star formation can noticeably affect only at the boundary of the outer part of the galactic disk, while its influence is negligible at large distances.

- I will also take into account the fact that in the outer part of the galactic disk, gravitational interaction is negligible compared to the interaction due to elastic collisions (see Fig. 1, as well as the introduction in the article). One can see that “Keplerian” curve drops dramatically with distance, while the observed rotation curves demonstrate presence of some force much greater than gravitational force. I make this jbservation (about the insignificance of the gravitational force) solely for the sake of simplicity of calculations, in order not to clutter up the calculations with unnecessary small corrections and insignificant details. Moreover, this simplification of our model also plays against us, because if gravitational force was considered, then the gas in the galactic disk would be even more bounded with the host galaxy. Thus, we again consider the worst case for us.

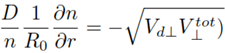

Considering all of the above, after simple transformations of expression (5), one can obtain the following equation, which gives the relationship between the tangential velocity (rotation curve), on the one hand, and the gas density, as a function of the distance from the center of the galaxy, on the other hand:

Having chosen such galaxies for which both measured column densities and rotation curves are available, using this equation, one can implement one of the following two different ways: 1) take the measured column densities and using the resulting equation calculate the rotation curve, then compare them with observations, or 2) take measured rotation curves, substitute them into the resulting equation and calculate the column densities, which then should be compared with the observed ones. If a functional relationship between these two quantities is found through the above equation, this will mean that, in fact, the dynamics of the gas in the outer (R > R_25) regions of the disk is determined predominantly by the kinetics of the gas.

In my work, I follow the second way. Two galaxies were taken, for which both rotation curves V(R) and measured column densities N(R) are available in literature. Based on the measured rotation curves, the column densities were calculated for this significantly different in size and masses galaxies (see Figs. 1.2.3.4 in the article). The coincidence with the observed distribution of gas density turned out to be excellent. This indicates the validity of the assumptions made and the correctness of the model. Thus, the “non -physical” rotation curves of galaxies are simply tailwinds of rarefied gas, the dynamics of which is completely described by gas kinetics. One can conclude that DM is not required to explain RC of S-galaxies.

A few words about young stars, born in the outer parts of galactic disk, should be said. These stars are formed from gas and, at the time of birth, receive its average momentum. Elementary calculations in the framework of classical mechanics show that such stars will be gravitationally bounded with host galaxy. However, they will follow not circular, but elliptical Keplerian orbits. When constructing a comprehensive model, it should also be considered that the speed of star formation is associated with the density of gas. If the density falls exponentially with the distance (and this is the case), then the star formation rate will also fall exponentially as distance increase. In other words, new stars in the outer part of the disk are almost not formed. It is likely that rare single stars observed in the outer parts of galactic disks were formed in the underlying layers and moving along elongated elliptical Keplerian orbits temporarily moved to where they are observed.

Summary.

Summarizing the discussed above, it can be argued that the rotation curves of the galaxies are formed without the presence of DM. To understand this, it is enough to assume that the rarefied gas obeys the laws of gas kinetics. In my modest opinion, the requirement of compliance with the obvious laws of physical kinetics is slightly less unusual than the requirement of the existence of DM in galaxies.

To model a spiral galaxy, three very different areas of galaxies can be separated:

1) R <R_0 (here R_0 is of the order of the value R_25; for a galaxy represented at Fig.1, it consists approximately 10 kpc.). This part of disk is populated mainly by stars (described as an ideal collisionless gas in gravitational field). Of course, the stars here are orbiting in consequence with the Kepler law. The influence of real gas is negligible due to its small abundance and the absence of interaction gas – stars.

2) R ≈ R_0. This is a transition area where an active star forming processes take place. For this reason, the gas is depleted, and for calculating the rotation curves, many subtle details (such as the structure of galactic arms, the star formation rate, the temperature of the gas, etc.) should be also included.

3) R > R_0. This area of our interest in which gravitational interaction no longer has a decisive value. Here, the rotation curves are determined by the gas kinetics and the rotation speed V┴ = V_K + V_d, where V_K is Kepler velocity (it is placed as a boundary condition at the distance R ≈ R_0), and V_D is the dynamic speed of the gas stream due to diffusion. In this outer part of galactic disk, the gravitational interaction between gas and galaxy is weak. In consequence with law of gas kinetics, the gas moves along a circular orbit, forming tailwind. It is this tailwind that forms the “non-physical” rotation curve.

In accordance with the above, the problem of DM can be considered as solved. There is simply no place for dark matter in the Universe, because if it existed, the rotation curves of galaxies would be dramatically different from those we observe. The history of dark matter, which has more than 90 years, is over.

Discover more from Reflections on Modern Physics

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

UNA PERSPECTIVA FILOSÓFICA SOBRE LA FUERZA DE GRAVEDAD Y LA ENERGÍA OSCURA

por: Diego Hernán Moscoso Sanginés UriarteDurante los años 1873 a 1883, el empresario, filósofo, politólogo, sociólogo, antropólogo, historiador, periodista, y teórico revolucionario comunista, Federico Engels escribió un manuscrito inconcluso que no publicó en vida, titulado “Dialéctica de la naturaleza”1, En épocas posteriores, Eduard Bernstein le pasó los manuscritos a Albert Einstein, quien pensó que la ciencia era confusa (particularmente las matemáticas y la física) pero el trabajo general era digno de su publicación2.El manuscrito lo divide es dos secciones, que las denomina “Esbozo de un plan conjunto” y “Esbozo de un plan parcial”, en la segunda sección el contenido habla de física, biología, química, astronomía y matemáticas, Uno de los temas que aborda es: Gravitación; cuerpos celestes; mecánica terrestre. Ahí indica; “Generalmente, se acepta que la gravedad constituye la determinación más general de la materialidad. Lo que vale tanto como decir que la atracción es una propiedad necesaria de la materia, pero no así la repulsión. Pero atracción y repulsión son tan inseparables la una de la otra como lo positivo y lo negativo, razón por la cual podemos ya predecir, partiendo de la dialéctica, que la verdadera teoría de la materia asignará a la repulsión un lugar tan importante como a la atracción y que una teoría de la materia basada simplemente en la atracción es falsa, insuficiente, a medias”. Más adelante: “Atracción y gravitación: Toda la teoría de la gravitación descansa sobre la tesis de que la atracción es la esencia de la materia. Afirmación necesariamente falsa. Donde existe atracción, tiene que complementarla necesariamente la repulsión. De ahí que ya Hegel afirme con toda exactitud que la esencia de la materia es la atracción y la repulsión. Y, en efecto, va imponiéndose cada vez más la necesidad de comprender que la desintegración de la materia llega a un límite en que la atracción se trueca en repulsión y, a la inversa, la condensación de la materia repelida a otro en que se convierte en atracción.”Aquello tiene sentido con la definición de energía oscura :”En cosmología física, la energía oscura es una forma de energía que estaría presente en todo el espacio, produciendo una presión que tiende a acelerar la expansión del universo, resultando en una fuerza gravitacional repulsiva3″. Por lo que sugiere que atracción y repulsión son dos efectos de un mismo fenómeno, como el electromagnetismo. Entonces, atracción y repulsión son resultado del movimiento, de esa manera, el movimiento cósmico genera la fuerza gravitatoria atractiva y paralelamente la fuerza gravitatoria repulsiva. Sin embargo, la dificultad radica en las nomenclaturas elegidas por la academia científica para denominar ambos fenómenos naturales, por un lado, la gravitación se consideran una fuerza, mientras que el fenómeno repulsivo se le consideran energía, actualmente llamada energía oscura. Sobre esto, Engels dice: “Por tanto, si, según la concepción moderna, la energía no es más que otro nombre dado a la repulsión… la fuerza aparece aquí como otra manera de expresar lo contrario de la repulsión, o sea la atracción.”Además, según Engels: “La forma fundamental de todo movimiento es, según esto, la aproximación o el alejamiento, la contracción o la expansión; en una palabra, la vieja contraposición polar de atracción y repulsión…Todo movimiento consiste en el juego alternativo de atracción y repulsión. Pero el movimiento sólo puede darse cuando cada atracción singular se ve compensada por la correspondiente repulsión en otro lugar distinto. De otro modo, uno de los lados acabaría predominando con el tiempo sobre el otro, con lo que el movimiento cesaría, a la postre. Eso quiere decir que todas las atracciones y todas las repulsiones se compensan mutuamente en el universo. Por consiguiente, la ley de la indestructibilidad y la increabilidad del movimiento cobra, así, la expresión de que todo movimiento de atracción en el universo se ve complementado por un equivalente movimiento de repulsión, y viceversa; o, como lo expresaba la filosofía antigua -mucho antes de que las ciencias naturales formulasen la ley de la conservación de la fuerza o de la energía-, de que la suma de todas las atracciones operadas en el universo es igual a la suma de todas las repulsiones.”.Entonces se puede concluir qué, lo que estamos mirando en el cosmos no son interacciones de la fuerza de gravedad y la energía oscura, sino, el movimiento de los cuerpos celestes, de donde la atracción y la repulsión son sus cualidades intrínsecas.

LikeLike

Estimado Dr. Diego Hernán Moscoso Sanginés Uriarte! Muchas gracias por su amable comentario. Me da mucho gusto de verlo aquí.

Desafortunadamente, es poco probable que puedo responder satisfactoriamente a su comentario porque, por un lado, no soy especialista en el campo de la historia de filosofía, y por otro lado, todo mi blog está dedicado exclusivamente a la fisica contemporanea y, por lo tanto, el mismo formato de mi blog no supone tales excursiones históricas y filosóficas. Por lo tanto, lo más probable es que no puedo responder completamente a su comentario, pero intentaré hacer lo posible.

En primer lugar, me gustaría centrar su amable atención en el hecho de que la dialéctica no puede ser reconocida como un modelo completo, debido a su estructura binaria interna. Pienso yo, que reducir la naturaleza real solo a dos principios que interactúan (a la tesis y la antítesis) es una demasiado fuerte simplificación. En realidad, si considerarémos un sistema más cuidadosamente, entonces la tercera, la cuarta y etc. partes interactuantes de la misma, siempre aparecen visibles. En esencia, el punto principal es la precisión de la descripción del sistema.

Por esta razón, me parece que no sería completamente justo de considerar inicialmente la gravedad desde el punto de vista de la dialéctica. Inicialmente, no sabemos cómo se organiza la naturaleza y, por lo tanto, es imposible revelar el 99% de las posibles opciones desde el principio, reduciendo la ventana para construir modelos solo dentro del marco restringido por la dialéctica. Sin embargo, esta es mi opinión personal y no me atrevo a insistir en ella.

Como ejemplo para ilustrar mi punto de vista, puedo ofrecer electromagnetismo. En la primera aproximación hay fuerzas eléctricas atractivas y repulsivas, y el camino simplificado de la consideración dialéctica trivial, parece muy tentador. Sin embargo, tras un examen más detallado, notamos que este enfoque no es cierto (no funciona) ya que las partículas muestran un momento dipolar. Con una consideración aún más exhaustiva, vemos momentos quadrupolares y octopolares, así como multipoles de un orden superior. Por lo tanto, en el electromagnetismo, la interacción no puede reducirse a pura atracción o repulsión. Eso significa que su enfoque dialéctico no es del todo correcto, y puede ser considerado solamente como una primera aproximación.

En mi opinión, sería demasiado audaz esperar que la naturaleza de la gravedad sea más primitiva que el electromagnetismo. Puedo suponer que más bien lo contrario.

Por esta razón, la conclusión final de su comentario es muy difícil de considerar indiscutible. Al menos no confiaría en la lógica de su conclusión dialéctica.

Gracias de nuevo por el comentario.

LikeLike